Educators understand and apply knowledge of student growth and development.

During my formative practicum placement in a Math 8 class, I learned an important lesson for dealing with behaviour. My first week in the class was by far the hardest–I did not yet know all students by name, they didn’t know me, and we all had masks on. Like any situation where everything is new (a new job, a new school, eating at a new restaurant, getting a new puppy), there is usually an initial period where the waters are tested and their boundaries shaped. In my case of entering and teaching a new class of students who have preexisting familiarity and relationships amongst themselves, I find a professional demeanor and an open mind is usually a good place to start. As time passes and and the blinking eyes and names on the attendance sheet start to reconfigure into individuals with stories and personalities, it becomes far easier to adapt my own behaviour to fit the needs of the individuals and the class as a whole. At the time, my experiences with students, from the position of EA and teacher, had been more or less positive–I had not yet found the student that excelled at pushing my buttons, until this class.

During my first week in this Math 8 class, I started to get to know the students and learn more about their personal interests and personalities. Not everyone was gleeful to communicate with me at first, but it might be weird if they all were at that age. Nevertheless, no one was overly rude nor confrontational. One of the relationship building methods I have been practicing while teaching are Name Tents (Figure 1) and exit slips (Figure 2). A name tent is simply a piece of paper that is tri-folded into a tent shape and is used as both a placeholder for students names and as a communication device. Students are asked to draw and decorate their names on the blank side of the paper and then keeping it on their desks for identification. On the back side is a place for exchanging comments between teacher and student. Each day, I would give the students some kind of prompt that could be personal or academic (i.e., What is one thing you want me to know about you? What is the strangest thing you’ve ever eaten? What was the most engaging part of today’s class? etc.) and the students would write their response in the “Comment: (Student)” section to which I would respond back in the allotted spot below “Response: (teacher)” (see Figure 1).

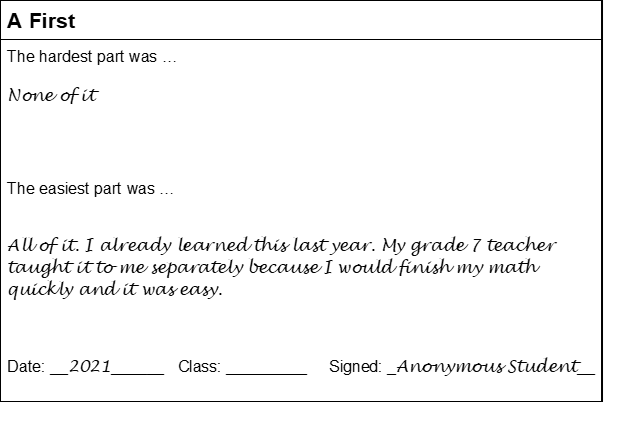

The first time I tried using the Name Tents was in a Grade 11 Chemistry class and I found the experience useful and positive. In the grade 8 class however, it provided a student who was normally quiet and non-confrontational an outlet to be rather rude to me. In class, this student had always been respectful and seemed pleasant enough so I was taken aback when, on more than one occasion, I read confrontational and inappropriate comments directed at me in the Name Tent. At the time, I knew the behaviour needed to be addressed, but I didn’t yet understand where it was coming from–not until I read the student’s response to an exit slip I assigned at the end of class one day that is (Figure 2). Looking at figure 2, it is clear that part of the reason this student was acting out was because the learning wasn’t challenging enough to be engaging. Although I found his mode of displaying his detachment from the work passive aggressive, I also recognized that focusing on the math rather than the behaviour might be an effective approach, so that is what I tried.

To address this student’s comments on his exit slip, I prepared a set of extension math problems for the following day that were related to the topics being covered (the Pythagorean Theorem and Surface Area) that would hopefully both deepen his learning and get him interested. I always do these problems before giving them to students and had formed quite a collection of relative extension problems to use. The next day, I thanked the student for the response he gave on the exit slip and that I had prepared some problems that he might find more engaging. I also explained to him that I still needed a demonstration that he was understanding everything we were working on as a class so the deal was, once he demonstrated competence and understanding (through responding to small number of math problems using personal whiteboards with the rest of the class), he could spend the rest of the time working through extension problems (Figure 3). I would provide these questions discretely so that he wouldn’t feel isolated and so that other’s would be less compelled to compare their own successes with problems to these.

The result of listening to this student and acting on his feedback was profound. Not only did the behaviour disappear completely, but at the end of that day he both thanked me and said how much it meant to him that I took the time to find more interesting problems for him. Previously, we had briefly discussed music in the class and he knew that I played and composed and I knew that he was in the school band where he played and composed his own works. The following day after first providing the differentiated instruction, he brought a piece of music he had been working on to show me and even emailed me a digital copy. With the behaviour gone, we had formed a new relationship, and one where he felt heard. This may not always work; however, the success of focusing on this student’s strengths rather than behaviour gave me an important lesson as an educator, and one that I hope to continue with into the future.