Numeric and Scientific Literacy

My competence in using and understanding numeric and scientific literacy is something I value highly as both an educator and a human being.

Throughout my life, I have fostered and indulged a persistent attraction towards discovery and understanding of the world and people in it. I would speculate that my primary drive towards exploring curiosities stems from the stories that have affected me. As a child growing up, stories—whether they were orated, read, watched, or performed—were essentially a looking glass into an undiscovered or unfamiliar world to me; they provided otherwise inaccessible perspectives and bred inspiration towards a dynamic life. This curiosity became a craving to be part of something, or some things, and it took me down all sorts of roads, including film school for acting where I intended to make living telling stories of the human condition. It was not until later, after deciding to commit to an academic degree in the sciences, that I began to utterly understand the power of structuring my curiosities through the processes and models of scientific thinking.

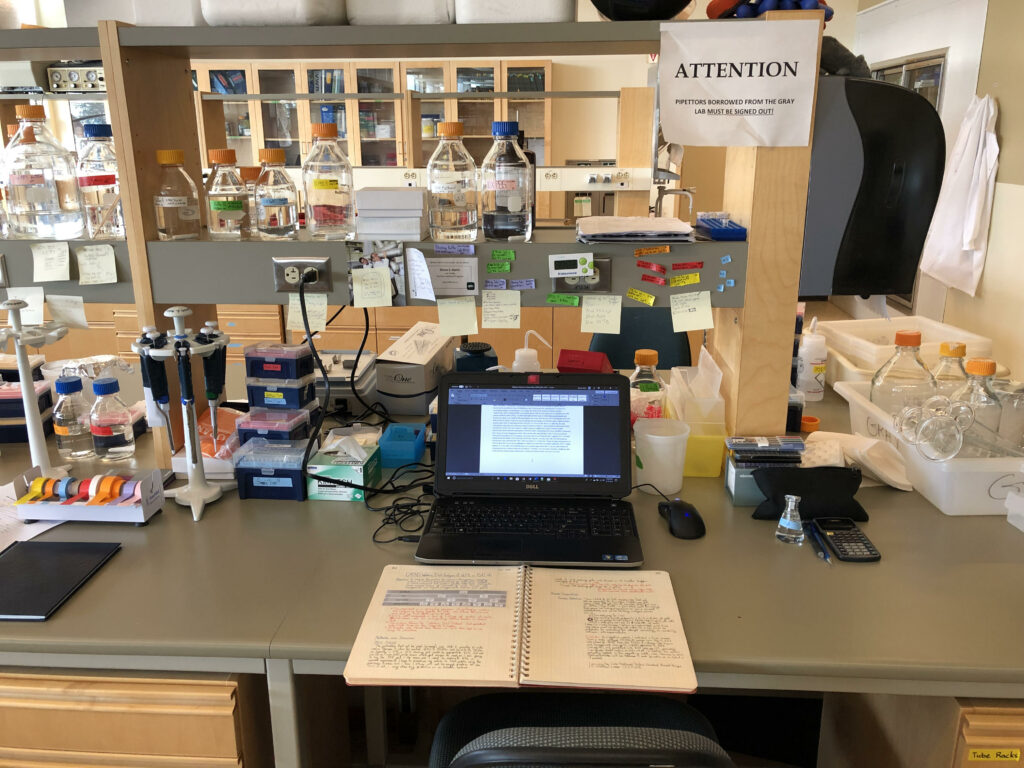

Numeric and scientific literacy is a way of approaching or looking at something rather than the amount of scientific or numeric facts or fields someone understands—in this case, the content I do know occupies only an infinitesimal subset of what is, or could be, known and rather, I am competent only in an approach towards the unknown and not the unknown itself. Through my training in biochemistry and molecular biology, I was provided the opportunity to work in several research labs that studied a diverse range of topics including the diet analysis of local moose populations to the thermogenic mechanism of a pituitary hormone on certain fat cells. Science begins with a question and develops with the scientific methodology of falsifiability, reproducibility, data analysis and so on. It is both fascinating and frustrating to understand how and why experimental data is modeled an analyzed in some way. Through conducting my own research, I have experience in statistical modeling of data sets and have become familiar with innumerable modeling approaches available to data analyzer. Not only is there not a “standard” method for analysis, but professional statisticians also seem to be in continuous disagreement over what type of model is the best used for some data set. In today’s 21st century world, life is accompanied by a constant stream of statistics influencing our perspectives and opinions through media and networking, and unfortunately, very few take the time to consider where a number comes from or how/why it was reported. For example, are COVID-19 mortality rates actually good metrics for judging virulent severity when they do not consider the cost of long-term treatment for patients who acquired chronic illnesses from the virus?

Developing competence in numeric and scientific literacy has provided me with the language, tools, and approach required to navigate the existing body of academic and scientific literature. The universe is filled with infinite questions and discoveries, and despite knowing or understanding what is in the literature, understanding the approached required to develop a point of understanding is where the real competence lies, and it is thus pertinent to the teaching of science and numeracy in education. Although much of my competence in numeric and scientific literacy has been developed personally or through university classes and research, I have been learning new ways of communicating scientific concepts and processes to secondary classrooms. This process fundamentally focuses on identifying key aspects of science and numeracy that can be phrased simply enough to understand and delivered in a form that can be explored, interacted with, or demonstrated. Demonstrating agency in the subjects one teaches, beyond the scope of the class, allows the educator to extend the limits of exploration within the educational space by handing more complex or broad student questions, providing context or examples to concepts, and having confidence to say “I don’t know, lets find out.”