First Peoples Principles of Learning have been foundational in guiding my pedagogy and practice.

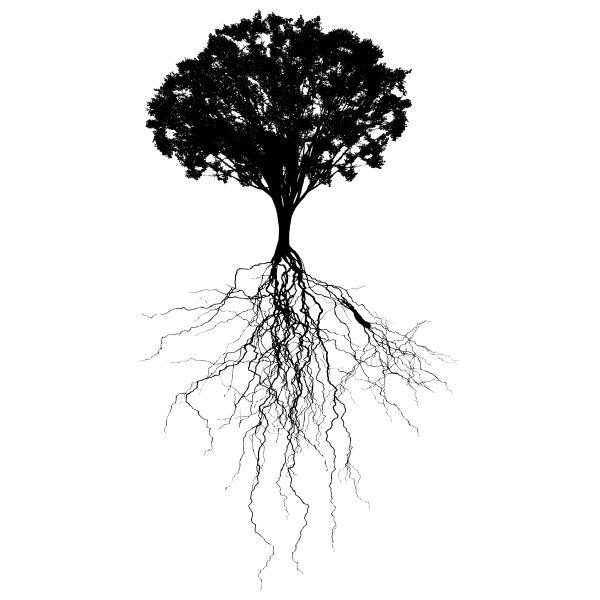

The model I’ve chosen to demonstrate my understanding of Indigenous Education and how First Peoples Principles of Learning are the foundational roots that supports learning.

I have chosen a tree as a model of how I have learned to use First Peoples Principles in my practice, and specifically, it is the roots of the tree that are representative of the FPPLs.

During my 10-week summative practicum, I was tasked with teaching a science curriculum to two grade 9 classes at College Heights Secondary School. Prior to starting, I knew that I wanted to take the learning outside as much as possible, and so I made the decision to start with the Ecology unit first, as it was late September, and the grounds were starting to undergo the autumn transformation towards winter. I developed a project that would take place outdoors and would be ongoing throughout the ecology unit; I called it “Land Quadrants.” This project required students to go out into the school grounds in pairs and select a 1m X 1m plot of land that they could return to each day and apply their learning and build skillsets within the curricular and core competencies. Below are some examples of how FPPLs were foundational to this practice.

One group’s land quadrant. Images were taken only 2-weeks apart (Top: end of Sept; Bottom: mid Oct) but show clear signs of changing seasons.

Learning ultimately supports the well-being of the self, the family, the community, the land, the spirits, and the ancestors.

The act of going outside each day is not always comfortable, but it truly does potentiate health and wellness. Getting to know the nature in our community, breathing in fresh air, gaining physical exercise, and refining the senses to widen our perspectives is deeply supportive the self and more. This information becomes rooted in individual identity and is passed on directly or indirectly through interaction.

Learning is holistic, reflexive, reflective, experiential, and relational (focused on connectedness, on reciprocal relationships, and a sense of place).

To learn something is to learn a part of something. There is nothing discrete about characteristics of the natural world we learn about. From a First Peoples perspective, it may be said that everything is interconnected and that nothing can be affected without having some degree of influence on what is interconnected with it. To learn the name of a greenhouse gas in class is perhaps a simple fact but going outside and feeling water vapour in the air on the skin, hearing birds chirping as they breath out carbon dioxide, or seeing leaves of different shape and size reflect vibrant green light as they absorb other wavelengths from the sun to produce sugar and oxygen makes the learning holistic. Students work through reciprocal relationships with one another to apply their learning through experience that directly develops a sense of place; they do this every day.

Learning involves recognizing the consequences of one‘s actions.

As mentioned, the Land Quadrant project was highly focused on the interconnectivity ecosystems, which includes us as human beings who live on and interact with the land. When we went outdoors everyday, a large emphasis was put on recognizing the impact of our actions on the land and developing respect and appreciation for it. We would then reflect on certain aspects or actions that could lead to immediate or long term consequences, and what we could do to act in such a way that a balance is restored.

Learning involves patience and time.

One of the curricular competencies that this project focused on was learning to collect reliable data. Often in student labs, they will do their data collection during the allotted time during a single class and analyze it later. This project required students to collect data every day for over a month such that they could begin to identify patterns of change and make correlations between different data sets. Students ability to collect reliable data vastly improved during this course of time, and it also required them to commit to a data set that was collected over many days rather than one that could be collected all at once.

To return to the model of the tree, I will reiterate that the roots are the FPPLs that supports the learning above. The roots interconnect with everything within the tree and outside of the tree. The roots not only interconnect the tree with the environment but support the tree (learning) within it. The trunk is more like the curricular and core competencies—the skillsets that learners “do” to learn and connect ideas together and themselves with the world. These skills are supported and developed through the FPPLs. Finally, the branches and leaves culminate the knowledge of the learner(s). To describe an idea well (to build a strong branch with spectacular vibrant leaves), the learner must make a connection to it (experience it, have memory of it, connect it to other knowledge, feel it—these are the FPPLs) and be able to communicate it (these are the core and curricular competencies where the learner must develop skills such as writing, story telling, and more).