Items of learning:

- COVID-19 and Learning Cohorts according to Bonnie Henry and Teri Mooring

- Koh-learning in our Watersheds

- Using the iNaturalist app in and out of the classroom.

COVID-19 and Learning Cohorts according to Bonnie Henry and Teri Mooring

This past Friday, I was fortunate to participate in the Classroom to Communities (C2C) annual conference during the provincial PSA Pro-D Day. To start off the morning, my personal assumptions around the BC school cohort learning group model being ineffective as a preventative measure for COVID-19 transmission was confirmed by BC Teachers’ Federation (BCTF) president, Teri Mooring, following her conversation with BC Provincial Health Officer, Dr. Bonnie Henry. This conversation was influenced by the recent COVID-19 outbreak in a Kelowna high school which caused infection and hundreds and staff to self-isolate. Although acknowledgement of the learning group model’s lack in efficacy came as no surprise, I learned—and found useful—how the terms exposure, outbreak and cluster are defined in relation to contact tracing. A school exposure requires that someone, positive for the viral agent, from outside of the school comes into to the school. An exposure is what occurred in SD57 following a reported exposure at Prince George Secondary School (PGSS) in Prince George. Fortunately, the PGSS exposure did not lead to an outbreak (exemplified by the Kelowna high school), which requires that multiple people be exposed and positively diagnosed for the viral agent. An outbreak is closely related in definition to an epidemic; however, it differs in that it is used more often to emphasize geographic location. Finally, a cluster is essentially a small outbreak, where one or two people are exposed and positively diagnosed. I am pleased to have learned also that the BCTF is pushing so that teachers have increased access to information around contact tracing and become part of the information sharing process.

Koh-learning in our Watersheds

Prior to attending my scheduled workshops, we—as participants of the C2C conference—were introduced to the Koh-learning in our Watersheds program developed through a UNBC-SD91 partnership and collaboration with “students, teachers, administrators, the Aboriginal Education Council of SD91, community partners and interdisciplinary researchers.” This program is a place-based program that is curricular based on local watersheds near communities in the SD91 jurisdiction. Panelists Dr. Berry Booth, Professional Biologist and UNBC research manager, and Jacelyn Boyes, high school science teacher in Fort St. James, are both involved in developing and implementing the Koh-Learning program in SD91. Although not indigenous himself, Booth was explicitly humble while presenting his work and discussing how to view conservation through community in collaboration with the fourteen First Nation territories and 4 secondary schools within SD91 and the Nechako Watershed.

Watersheds (lakes, streams, creeks, wetlands) are central to all of our lives and all watersheds present different functions, including movement of nutrients and minerals, spawning grounds for fish, ecological habitats, or any a multitude of other factors. The Koh-Learning in our Watersheds program (where Koh is the Dakelh word for waterway) is a program directive for both indigenous and non-indigenous students to become stewards of change and connection to their local environments and communities so that the future is empowered, informed, and aware. Booth is particularly attentive to the protection of the endangered salmon habitats and began developing the Stream Keepers program as component of the Koh-Learning in our Watersheds program. Stream Keepers was designed to train teachers in how to use specific streams in education and to get students out and into the streams collecting data, learning, and contributing to restoration. Booth highlighted that a personal challenge, when developing the program, was centered around getting away from linear thinking, using the “square peg, round hole” analogy. Specifically, he was referring to how the model changed as it was developed. In the original model, they were going to use four small streams in four different communities; this was perfect for the school in Vanderhoof because a model stream ran a moments’ walk from class, but less perfect in Fort St. James where the stream was much larger and posed safety challenges. Furthermore, feedback from the collaborators in Fraser Lake questioned why they would bother finding a little stream when there was a giant lake in the backyard. With these considerations, it was clear that instead, teachers needed to figure out what would work best in their particular communities (wetlands, creek, lake, etc.) that would allow for inter-school overlap. The takeaway lesson from this process was that we, as place-based educators and community members, need to be able to adapt our systems to let them work and evolve on their own rather than try and take a square peg and pound it into a round hole. Boyes, who collaborated closely in the process with Booth, praised his work and effort both explicitly and through the success she demonstrated while implementing the program with her own students in a Grade 11/12 Geo-Environmental course she teaches. According to Boyes, students would be involved in a multitude of place-base practices including setting up and monitoring trail cams on streams and in the nearby John Prince Research Forest to monitor hummingbirds. She further spoke to expanding and integrating the program to the junior grades and said that one could teach the entire Grade 9 Science curriculum through Bees alone. If nothing else, you could tell she was engaged with fish ecology by the collage of student-painted fish backdropped in the camera frame of the Zoom.

Two students involved in the program personally spoke to their experience. The first student gave positive feedback noting the practical skills he gained, such as learning to set fish traps and chemically testing the water, and how the self-assessment and place-based work resonated with him. He elaborated to explain how real-world application and experience allowed him to explore why something does or does not work. I felt his comments were profoundly useful because they support my personal philosophy of learning which requires a spark of curiosity in concert with meaning in the process of exploration where things continually work or fail. A second student spoke praised the program for providing her an avenue to utilize her strengths and passion for art—she made the program logo! Furthermore, she highlighted her personal progress in developing social and leadership abilities and in the building of unlikely relationships and friendships that emerged as a product of this collaborative place-based learning system.

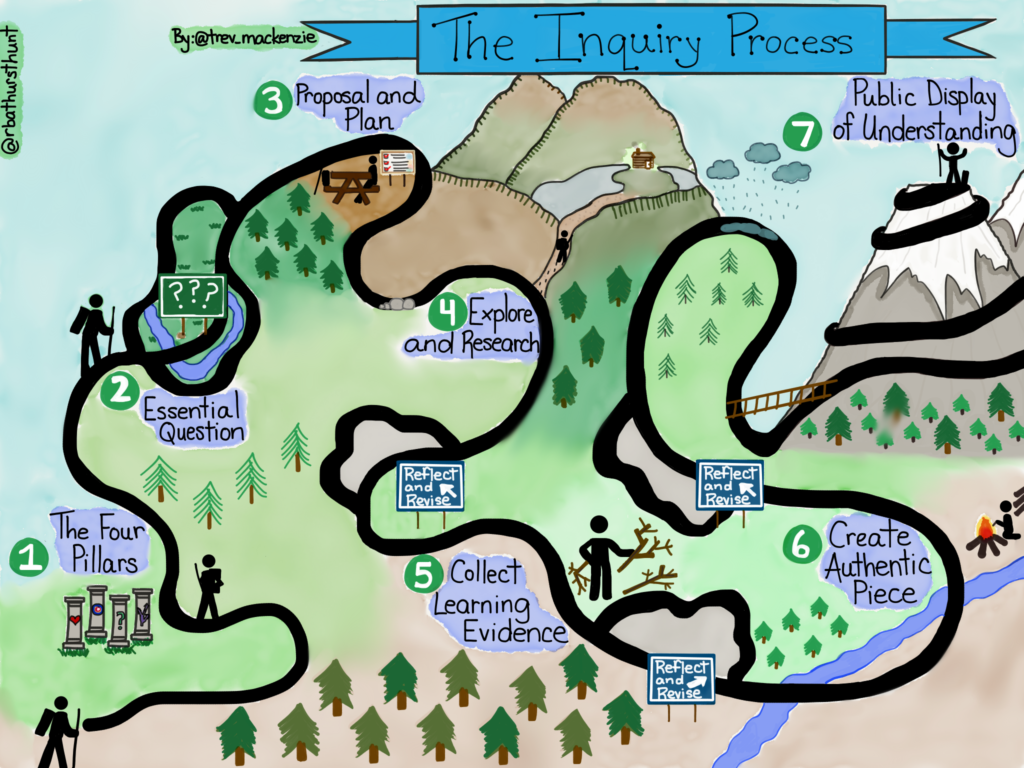

I find promise in the place-base model for curriculum. A sense of place are the emotions someone attaches to an area based on their experiences, according to Valemount Secondary School Counselor and Researcher, Dr. Shirley Giroux. Just as Dr. Booth explained how the processes of developing the Koh-Learning program required a step away from linear thinking and towards adapting our systems to let them work and evolve, learning involves allowing individuals the time and space for their curiosity and motivations to evolve and grow. Personally, I see the classroom as a functional and useful space for learning; however, it is missing part of the story—the practical space in which theoretical topics and ideas can be explored or perhaps the laboratory of life. A place-based model is a framework for students to take the principles, theories, and ideas developed in most classrooms and see how they manifest in real life—like in a stream. This provides more than a robust understanding, but that emotional connection called sense of place that is often absent from classrooms and textbooks. Perhaps the largest benefit of a place-based classroom is the gained opportunity for of differentiated learning. Students have all sorts of strengths and interests that makes life and humanity so robust; nevertheless, the teacher-to-student ratio is largely skewed so there is an obvious need for generalized learning curriculums and because of this, many traditional classrooms tend to privilege the students often labeled ‘book smart’ and deem the more restless, kinesthetic types as behaviours. The place-based classroom provides outlets for all types of learners because the parameters of opportunity are not constrained. Take ornithologists as an example: when studying birds, they contribute a large portion of their lives to academic study and learning, but when they are out in the field, they need to be able to visually (behaviour and identification), auditorily (bird songs), kinesthetically (handling), and creatively (drawing accurate representations) apply their knowledge which is only possible through practice. Students do not need to hone the abilities and knowledge of a trained scientist, but one can easily see the diverse attributes of students collectively applied to a curriculum to form learning that is robust, inclusive, and respectful.

Using the iNaturalist app in and out of the classroom

Before I finish, I would like to mention my favourite workshop of the day and how it gave me a brilliant tool for place-based learning. In the Exploring Nature with iNaturalist workshop, presenter Neil McCallum introduced the participants to the iNaturalist app which was developed by a Masters student from UC Berkley and uses image recognition software (like the automated categorization of your Google or Apple images for example) to identify taxonomy in nature. This free app allows the user to observe and identify organisms in nature to a degree of precision that reflects the quality of the image or audio input. The uploaded file is then cross referenced to a databased, geotagged, and stored on a public database. Geotagged identification is mapped for public access where any user can add additional input, corrections, confirmations, collaborations, and more. The data is also publicly available with defined quality parameters so it may be collected and utilized by researchers. For the classroom, a teacher can create a class account and have students perform and participate in projects while keeping their online anonymity; moreover, the geotag option allows the precise location to become generalized to prevent tags from marking student’s homes. There are many teaching resources available as well, including the City Nature Challenge and the BC Nature Challenge & BC Parks iNaturalist Project. For teachers looking to utilize iNaturalist with younger students (Grade 3 and under), there is another free app by iNaturalist called Seek, although I have not given this one a try. I have been enjoying playing with app and uploading my own images. I was also impressed to have received multiple responses from hobbyists and professionals in the community regarding my uploads. Furthermore, I was blown away by the apparent number of users found all over the globe while I used the interactive map portion called ‘Explore’. The place-based learning potential is explicit in the definition! Please check it out, even if you don’t plan to use it in a classroom!

This image is free for use under creative commons and is credited to

This image is free for use under creative commons and is credited to