During my EDUC 490 teaching practicum, I was placed in a Grade 8 mathematics classroom and DP Todd Secondary School. The experiences I’ve had in the classroom over the past 4 weeks have expanded my conceptualization of changing, or adapting, pedagogy to fit different learners in different environments. Having taught grade 11’s in Chemistry for my previous practicum, it became quickly apparent that some of my pedagogical approaches would need modification to fit the needs of the Grade 8 students at DP Todd. In general, some of the primary factors that affected pedagogy included the mathematics curriculum, the age and maturity of students, classroom management, the school demographic, the distribution of diverse learners and abilities, the mathematics department, attendance, expectations, the block semester system, the time of year, Math 8 being a required course, the effectiveness of student-choice, and student-centric approaches. Exploring and adapting categories such as these helped to expose some of my strengths and stretches which I am refining and working on in my teaching practices.

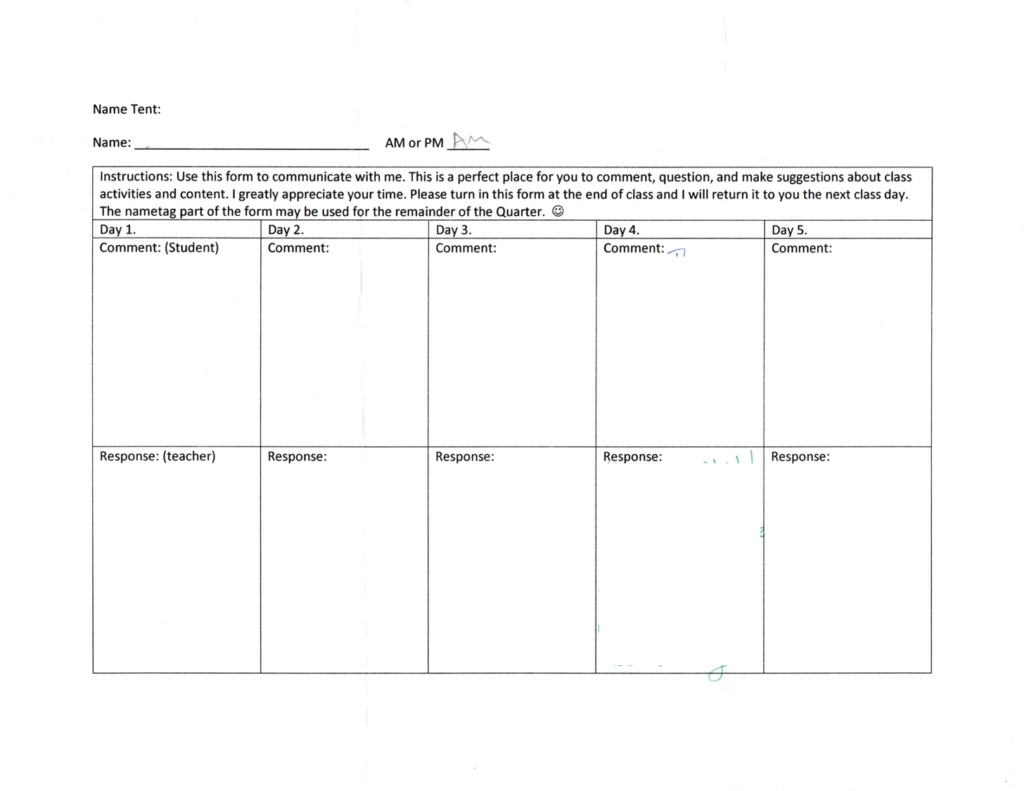

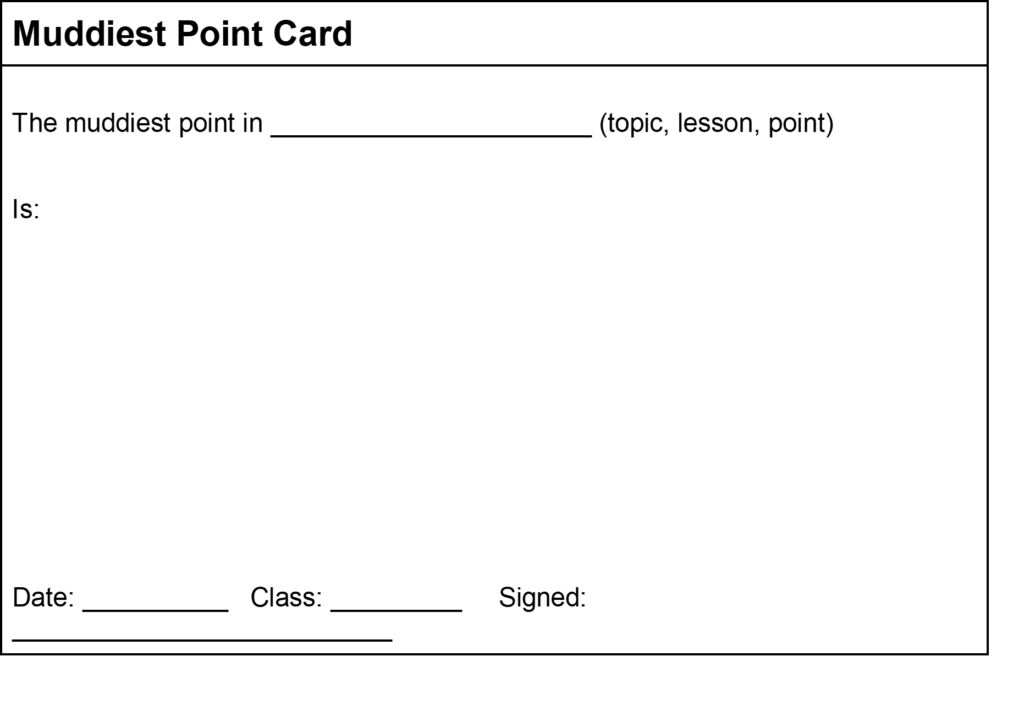

As a new teacher in training, I found myself entering classrooms with initial expectations based more in theory than practice, which of course is an inevitable consequence of academia. The teaching process then becomes one of inquiry—what actually works in practice? how does theory transform into practice? what factors of teaching will have the largest impact on student learning? how does a classroom change day-to-day? how long will something really take? Although my educational expertise is at an early point on a continuous growth curve, I would classify one of my growing strengths as the ability to recognize the power of relationship building in classrooms and how to apply it towards student growth and development. The first week of practicum was by far the most difficult. Because of the block semester system in place this year, the students had been learning around one another for at least 6 hours per day since September, making my position as an outsider exploitable for the initial days. To me, it was fascinating to experience how strongly getting to know the students, and having them get to know me, changed our practice over the four weeks. Something as simple as knowing students by name became immensely influential over classroom management practices, for example. Rather than simply calling students out by name for ‘misbehaviour,’ names were a powerful tool for personalizing the learning, individually focusing/redirecting attention, and integrating distracted students into the lessons. Furthermore, getting to know students allowed me to diversify the lessons. As mentioned, the distribution of learners in a grade 8 math class is larger than might be found in an elective academic course (say, Physics 12); as such, getting to know the students provided me with informational tools to tailor lessons to fit diverse needs. Throughout my practicum, I used a lot of exit slips that asked students to report feedback on their learnings and interests. Through these, I was able to quickly identify the students who were in debilitating fear of being singled out to answer problems in class, those who needed more challenging problems to stay engaged, those who really benefited from hands-on activities, those who took art seriously, those who “hated math,” and more. In the Pythagoras unit, I demonstrated some of the art that can be done with fractal trees using the Pythagorean theorem to help engage the artistically driven students. I created sets of extension problems for most lessons that were both relevant to the learning goals of the unit and also incorporated learning that was done in other units previously covered. One of the ways I knew these extension questions were effective was that, on several occasions, I had students stay in at lunch to work through them or take them home to complete (I did not assign any homework during my practicum).

As a new teacher, I am becoming better at my classroom awareness; however, it is something that has been a stretch in my practice so far, and a focus for improvement. The importance of multitasking, planning, and broad awareness are some of the characteristics of teaching that I am becoming more familiar with. My multitasking skills have never been something to brag about; in fact, I sometimes pride myself on my ability to ignore others to keep a singular focal point. In the classroom, however, I need to know what I am teaching, how it is being received, how I am positioned in the classroom, who is paying attention, who is responding to open questions, who is in the classroom, who is doing nothing because they forgot a pencil, what time it is, and so on—not only for the sake of learning, but for safety.

During practicum, one of the stretches I’ve been concentrating on is positioning myself in the classroom so that my classroom awareness increases. During lessons, I would often be standing at the chalk board writing out problems or examples while speaking. I might do something like write three problems on the chalkboard in increasing difficulty with the intention that everyone could get through the first, most could get through the first two, and few could get through all three. The distribution in difficulty gave me the time to move around the classroom to check student whiteboards (where they were working through the problems) and sit with students who needed guidance without a bunch of students finishing immediately and becoming bored (this was also an ongoing stretch to execute effectively). When sitting with students, I found it far too easy to forget the rest of the class and singularly focus on the student(s) getting my help. Having a concentrated focus was effective for a specific task, but it meant that I didn’t always notice what the rest of the class was doing during these times. One of the ways I have been working on my classroom awareness is how I go about positioning myself at students’ desks. For example, if a student sits near the front of the classroom, I worked at sitting across from them so that I faced the either the majority of the students or a portion of the room that required more attention. This required me to practice writing and drawing upside down quite a lot. Another issue was the chalkboard where I often led lessons from. The units we covered required me to make a lot of 3-dimenstional drawings, create problems in real-time, and perform all the mathematical calculations in front of an audience. Because of the focus required to smoothly execute my explanations or thought processes in writing, I found myself, on numerous occasions, face-to-face with the chalkboard, talking away to it as the classroom full of students watched the back of my head (or ignored the back of my head, I wouldn’t know). I have since been working on position myself such that my body and vision is in an intermediate state of facing the classroom and the chalkboard simultaneously so that my awareness is maximized—something that is getting better with practice but is still far from consistent.

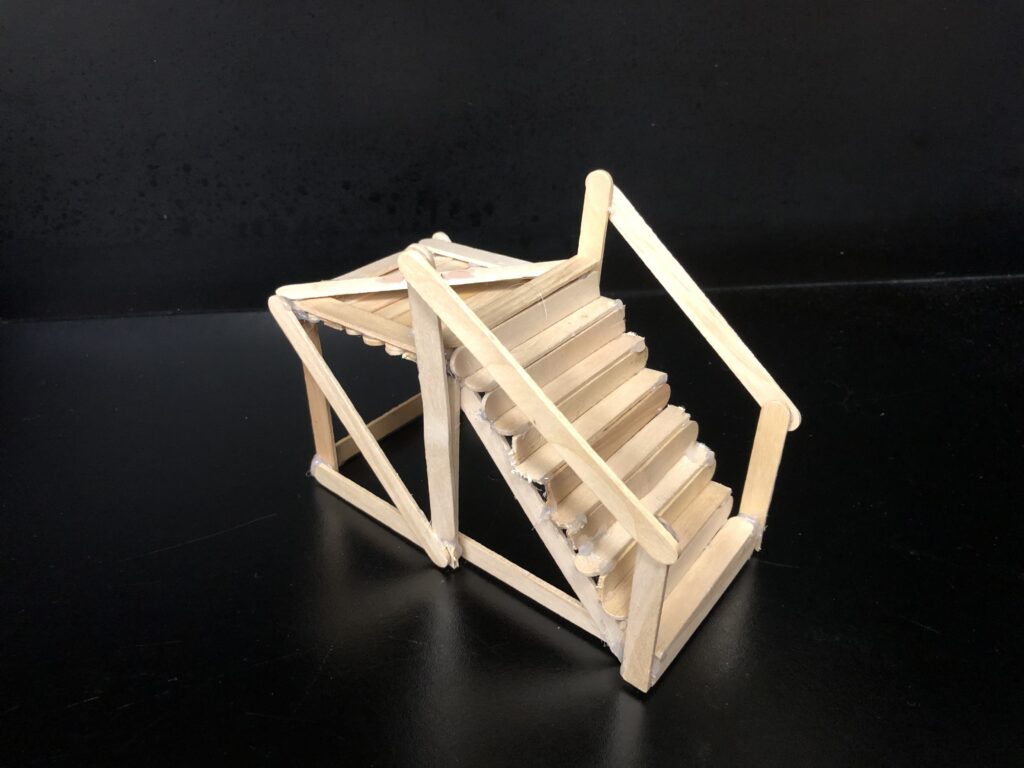

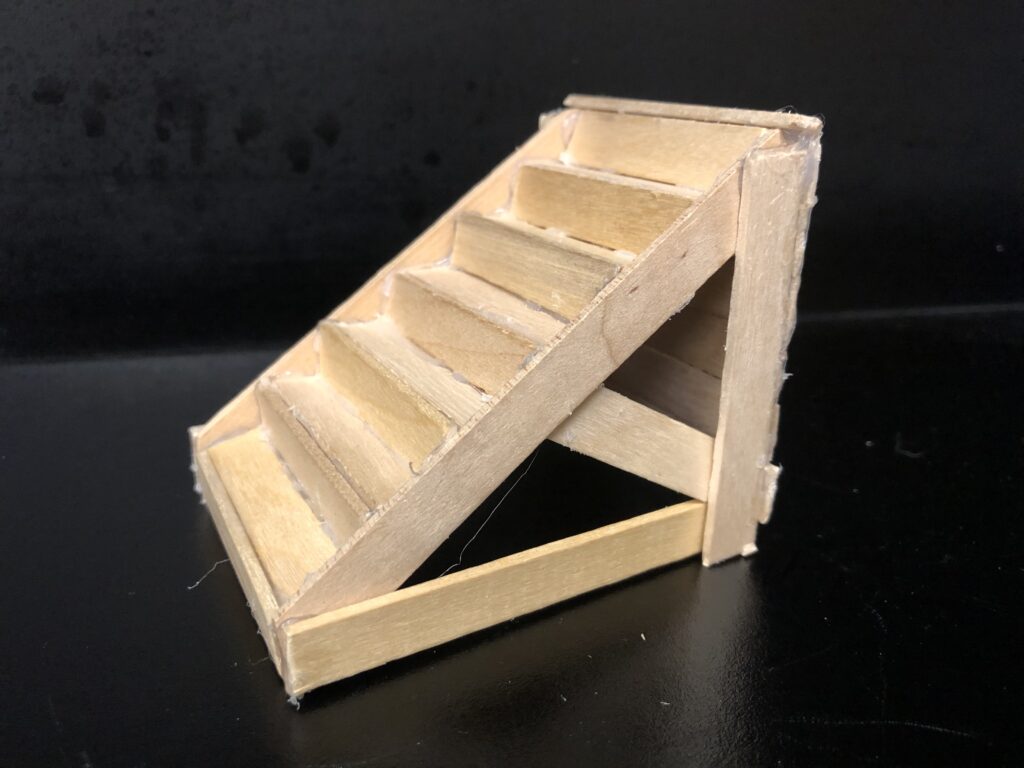

One of my favourite lessons during practicum was when students designed and built staircases out of popsicle sticks and hot glue, using the Pythagorean theorem as a design element as part of the Pythagoras unit. This was the first group project that I had given to students, apart from partnered labs in Grade 11 chemistry, and I found the experience valuable. The planning of the project took a lot of preparation to set up. The materials required were not fully available at the school, so I ended up purchasing most of them myself; furthermore, creating expectations, criteria, and an assessment rubric that both ensured students met the learning intentions while giving them a strong element of choice and freedom in their designs took careful consideration. Once set up however, the lesson planning was complete for roughly three days of teaching and the quality of learning was consistent. The reason this was my favourite lesson was that it was also the first time I had assigned a task and had every single student engaged and working on what they were supposed to without needing redirection. It allowed me the opportunity to comfortably circulate the room and inquire into the different ideas and processes of each group. It was interesting how great it felt to teach students who were doing something that engaged their interests because behavioural management became a trivial task and conversations about learning (projects) were far more accessible across all students.

This project was selected primarily because it was accessible to the diverse range of learners. Every student demonstrated investment in their designs and the complexities and intricacies they chose to include (or not include) were limitless. This student-agency led to creativity and a self-driven propensity to go beyond the minimum requirements of criteria; something nearly every student did. Students were asked to create a blueprint that demonstrated their use of Pythagoras as a design element; this required them to show how right angles can be determined using Pythagorean relationships and display all appropriate calculations. They needed to include sketches and calculations demonstrating right angled triangles in their design, create a physical model with popsicle sticks and glue, and finally a reflection which compared the theoretical model (blueprint) with the physical model (actual staircase). Overall, the reactions and feedback from this project were positive and the work developed demonstrated student creativity and individuality. It was also a valuable learning experience for me as a teacher because it illuminated a lot of problems that I did not account for prior to the experience. Although my planning was thorough and complete, the project required students to attend class and actually work on their projects in the allotted time. There were students who decided to miss days during our projects, another who started with a partner on the first day and was then gone for a week and a half, and finally a group of students who began their project together before deciding on the last day that they absolutely refused to work with each other for another moment and required alternative options. I facilitated the needs of all through adjusting groups, allowing students to borrow and take materials home to finish, extending due dates, and, in one case, providing a written unit test on Pythagoras that acted as an equally weight substitution to the project (the project took the place of a unit test for the rest of the class). Below, I have included the document provided to the students as the project guidelines in addition to some images of student projects.