When I consider the word footprint, I think of a trail of data which is inductive to some past event. Footprints may be intentional or unintentionally and can be covered up or fabricated. The data extracted from a footprint may be robust enough to provide clarity to an assumption or be partial and context-less leading to broad or false assumptions. Theoretically, I could look at a footprint in the snow and inductively reason information around their formations—potentially, the size and brand of boot, tread pattern, tread wear, if that person were turned-out or pigeon-toed, if they walked on their toes or heals, their estimated weight, how long ago they were formed, their location, direction, and speed, and so on. Footprints are a type of map of the past, and the data gathered is simply data; however, the way it is used can have far reaching implications in both the positive and negative.

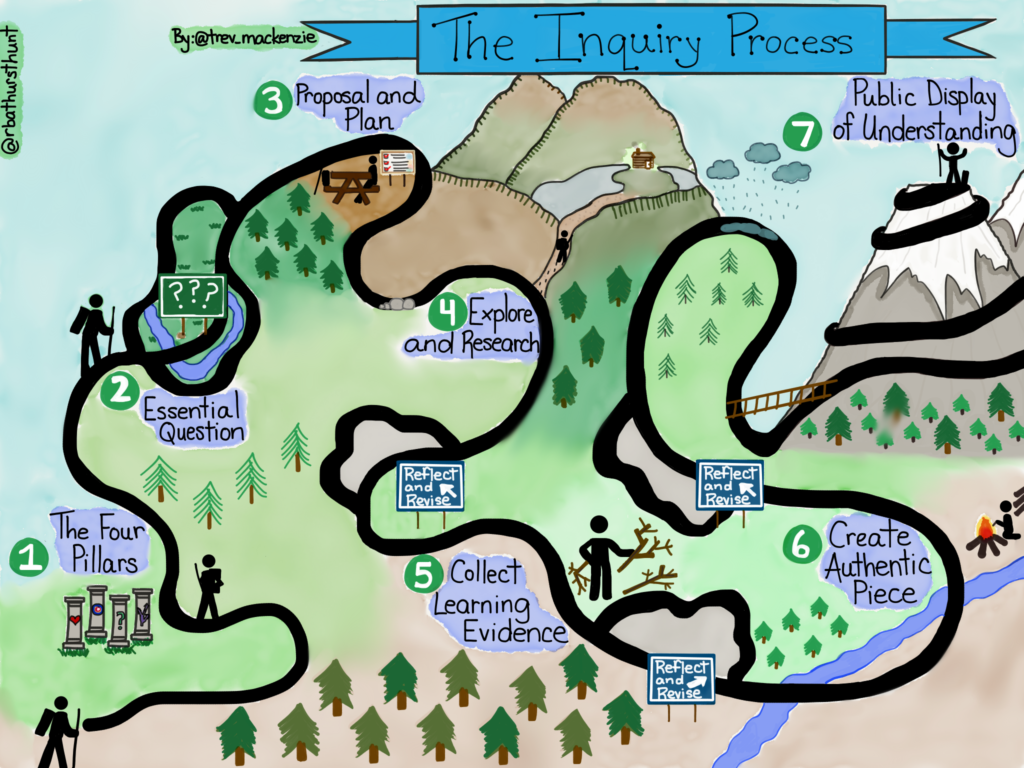

Today, we live the age of technology and the landscapes we leave footprints across expand beyond physical space and into the realm of the digital. So, what does this mean? What are digital footprints? Who makes them? Who can see them? Who can use them? What are the risks and benefits?

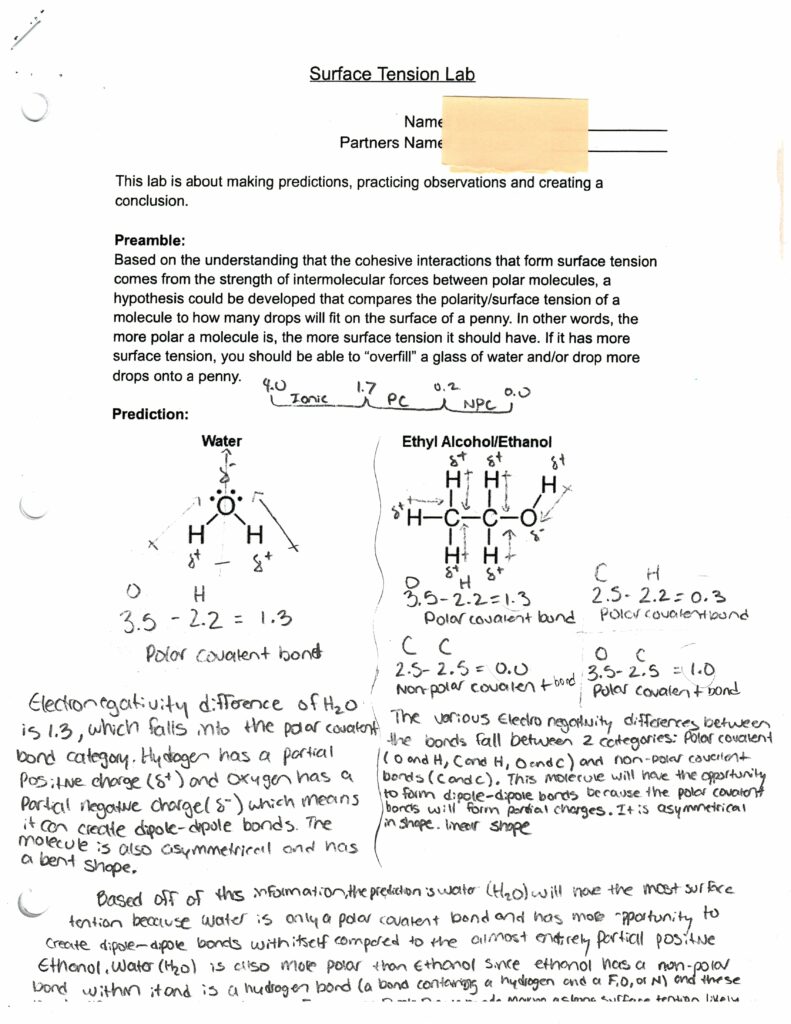

Digital footprints have been defined as “…a trail of data you create while using the Internet. It includes the websites you visit, emails you send, and information you submit to online services” (Christensson, 2014). Furthermore, digital footprints can be categorized as active and passive. An active digital footprint refers to a data trail that is intentionally and knowingly submitted by the user online—this could be posting in social media, sending an email, uploading files, pressing accept on a websites request for collecting cookies, and so on—where a passive digital footprint is a data trail left unintentionally—this could be websites that collect and track IP addresses, access location or proximity data, collect metadata, and more (Christensson, 2014).

This image was taken from directly from http://cognitio.ng/blog/digital-footprint-marvel-or-menace/ and is under a creative commons license.

As of 2019 in the US, 90% of adults were determined to use the internet on average, with an average of 100% of young adults (aged 18-29) using the internet (Pew Research Center, 2019). In American adolescents (aged 13 to 17), screen media use averages 6.5 hours per day, and in tweens (12 years of age), 4.5 hours per day (Joshi et al., 2019). To help with conceptualization, if there are 24 hours in a day and the average teen is asleep for 8 hours, goes to school for 6 hours, and spends 6.5 hours on screens, that leaves 3.5 hours remaining in the day for everything else, including eating, bathing, and chores. It is a safe assumption to say that, during the 6.5 hours of screen media use, teens are actively leaving behind digital footprints, but I would argue that both passive and active digital footprints are being formed for a far higher percentage of the day.

During my Observational Practicum in the first block of the B.Ed program at UNBC, I observed a constant flow of information and communication between students during class time in high schools. My snoopy eyes fell upon one teen’s smartphone screen that was displaying the popular Snapchat app (is it still popular? I don’t know…) and I observed more unopened messages that I personally receive in a month. The student would then quickly scroll through the snaps and quickly snap an image of something or someone in the class back to the sender, or senders. My observation revealed to me that students were communicating with rapid image exchanges during class and that many of the images being exchanged were of other students who did not know they were being observed. This exemplifies a level of caution and consideration that needs to be understood by citizens and students when simply existing in today’s world, regardless of one’s personal use and intentions with technology—simply by being around devices connected to the internet, digital footprints can be created and stored in many different formats (audio, video, text, location, heart rate, etc.).

This image was taken from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cambridge_Analytica_and_Facebook.jpg under a creative commons license.

Digital footprints both potentiate benefit and risk to users and bystanders. Social media platforms are generally used as active digital footprint creators where users intentionally upload and observe information related to their interests and intentions. These digital footprints can catalog memorable life events, share information like opinions, news, or media, and record exchanges between people. Media platform giants, like Facebook, also may collect user metadata as passive digital foot printing and use it to help personalize ads and recommended media; the flip side is that they can also use it to influence elections and economic growth or decay.

The largest caution to take to heart when conducting one’s self in public and online is that what one says and does may become a digital footprint, and that the digital footprint may be—and likely will be—immortal. This means that digital citizens must not only consider the immediate implications of their words and actions, but what that could mean to their potential futures (Buchanan et al., 2017). Teens love to provoke and test boundaries, and for the most part, we forgive them—that’s why students are suspended from school for fighting rather than being charged with criminal assault, for example. But with a fight, a lesson is hopefully learned, and life moves on, and the past stays in the past; with digital footprints however, that fight may be recorded on video and that video may come up in a future job interview, a med school application, or become I viral phenomenon that labels you for the rest of your life. Canadian Prime Minister, Justin Trudeau, is awfully familiar with digital foot printing after images of him in brownface from an “Arabian Nights” costume party, decades previous, resurfaced as a weapon against his political campaign in Canada’s previous federal election. I am quite sure that when he dressed up, Trudeau had no intention of offending anyone, nor anticipation that the immortalized images would come back to bite him, but the contexts of the past are different than the contexts of today, and the internet neither knows nor cares for timelines—it cares for sensationalism (warranted or not). I use the Trudeau example because it tells us something important—that no persons, even world leaders, are immune from the past once the data is in circulation, regardless of context or time.

This picture is a silly, but accurate representation of my time during acting school in Vancouver and will outlive me and my good friend Scott. It is part of my (and his) digital footprint. It is forever. So be it!

As a future educator, I take digital footprints seriously. Facebook was the first social media platform I began posting my thoughts, exchanges, and images to, back in 2007 near the end of high school. I have since gone through all of my social media platforms with a torch and incinerated as much damning evidence as I could. But what of the images of others I appeared in? What of the writings about me that I cannot delete? It is not that there was anything was seriously troubling, however, much of the language and images posted back then was that of a teenage boy making jokes, and not something I care to have stapled to my professional forehead. Currently, I consider my digital footprint to be something I expect others to access if they really try, and as such, I conduct myself as if anything could resurface one day. I no longer post personal information about myself or what I am doing in my personal life because I refuse help my future enemies out by providing any additional weapons. I am not paranoid; I just do not care for the risks of posting personal information anymore. I post to Twitter when I am asked to by the B.Ed. program instructors but otherwise stick to “liking” or “retweeting.” Apart from that, my digital footprint is something that helps me every day. My Netflix algorithms predict a fantastic set of films to watch constantly, I am always shown videos of amazing musicians work online, Amazon gives me pretty decent deal notifications relative to my interests, and my authorship on a scientific research paper will be permanently archived into the history of human knowledge and discovery. As an educator, I will communicate information on a broader scale and organize lessons with more efficiency and, because of the digital footprint it will leave, I will reflect with ease.

References

Buchanan, R., Southgate, E., Smith, S. P., Murray, T., & Noble, B. (2017). Post no photos, leave no trace: Children’s digital footprint management strategies. E-Learning and Digital Media, 14(5), 275–290.

Christensson, P. (2014). Digital Footprint Definition. TechTerms. https://techterms.com/definition/digital_footprint

Joshi, S. V., Stubbe, D., Li, S. T. T., & Hilty, D. M. (2019). The Use of Technology by Youth: Implications for Psychiatric Educators. Academic Psychiatry, 43(1), 101–109.

Pew Research Center. (2019). Demographics of Internet and Home Broadband Usage in the United States. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/internet-broadband/