Acting on “Tickets out the door”

One of the assessment strategies I have been employing over the last three practicums are ticket-out-the-doors (also called exit slips). This is a formative assessment technique (and a good lesson closer) that can be useful for collecting ongoing assessment, obtaining immediate feedback on the effectiveness of lessons, developing student self-assessment strategies (i.e., muddiest point), collecting student generated questions, making connections with students, and more. Ticket-out-the-doors can be quick and easy to implement at the end of any lesson; however, to have them be effective and not just “time fillers,” they need to be appropriately used and acted on.

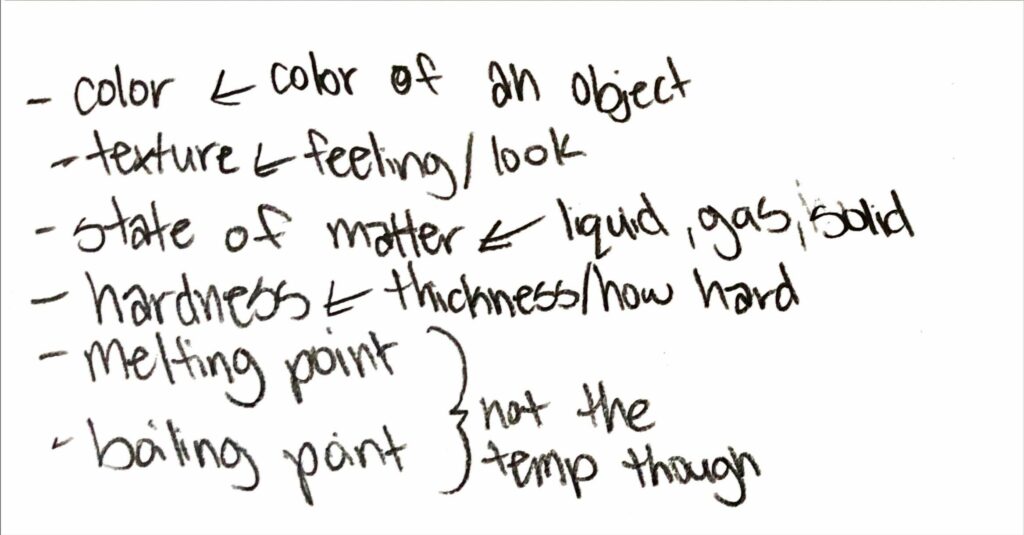

To start off the chemistry unit in science 9, we focused on improving curricular competency skills in planning and conducting through making qualitative observations of chemical and physical changes. I had planned it so that students would concentrate on making good observations (rather than inferences) during a lab activity prior to giving them a lesson on proper terminology that helps define chemical and physical properties and change; we would concentrate on identifying specific properties or changes afterwards. However, I wanted to do a quick pre-assessment on physical and chemical properties prior to starting the lab to see where the class was at, so I issued a ticket-out-the-door that asked students to look at a table of terms containing physical and chemical properties and then asked them to write down any of the terms they knew for sure, with a brief description/definition to show their understanding (figures below).

The next step was to scan through student responses and see if I could find any useful pattern(s). Through simple organization, I discovered that there were four terms (viscosity, combustibility, malleability, and reactivity with oxygen) that the majority of students either left off their list or answered poorly. The next morning—before we started our lab—we did a class activity where I showed a PowerPoint presentation, I had created the night before that had embedded videos exemplifying properties of these terms and I asked students to predict outcomes on their handout as we went through the examples as a class. To provide an example, one of the terms that held majority uncertainty was viscosity. The video embedded below shows “The Sci Guys” performing a viscosity race/ranking experiment of ten different liquids—the students had these substances listed on their handout and were asked to rank them from most to least viscous by assigning them unique values 1-10. I would then show the video to reveal the results. At the end of this class activity, students were to individually write their own definition for these terms, which I then used to formatively assess improved understanding. Students were also able to demonstrate understanding of these concepts in the observations made in the lab. The day after this activity and lab, students had a short worksheet as part of their lesson that asked them to identify chemical vs. physical properties and factors that indicate a chemical change—I have just described four sequenced forms of formative assessment (assessment for learning) on the same topic that allowed students to develop and demonstrate their learning in different ways because the instruction was highly differentiated. They will then go on to be assessed summatively during assessments such as other labs or unit tests.