My EDUC 391 practicum experience at College Heights Secondary School was both a positive and robust learning experience. I had the pleasure of teaching two units of the Chemistry 11 curriculum to a fantastic group of young individuals. Throughout the three weeks, 391 teacher candidates (TCs) were obligated to meet in groups of three to discuss and compare the progressions of our practicum experiences; these groups are called “Triads” and the three members are fixed. During my Triad’s weekly meetings, I learned about noteworthy characteristics like successes and issues that my peers faced in an English 11/12 and K/1 class. Although anticipated, it was fascinating to hear about the main areas of focus required for different age groups and subjects. For example, students in the K/1 class were highly diversified in terms of learning abilities, maturity, and socialization. Several students had Individual Education Plans (IEPs) and required specific supports to facilitate their learning. Consequently, there was an emphasis of focus towards ongoing classroom management. In the English 11/12 class, I learned of a student who was taking this class for their third and final time. This particular student read and wrote at problematically low grade level but had been actively turning their academic focus around in the recent year(s) and took agency over their learning with the goal of successfully graduating from high school. According to the teacher candidate (TC), this particular student supported themselves with a decent paying job that they enjoyed and hoped to continue with after high school; however, their continued employment was probationary on the student’s attainment of a high school diploma and this English course was a strict requirement. Because senior English is a requisite for graduation, the diversity of academic abilities across students is large and therefore required the TC to put high emphasis on differentiated learning in their teaching. The demographic in my Chemistry 11 class was certainly not homogenous; however, because Chemistry 11 and 12 and elected courses and require higher academic competence, the student diversity in both academic abilities and IEPs was lesser than my peer TCs. As such, I put high emphasis on personally knowing and understanding the concepts being taught so they could be presented to the students in dynamic and multifaceted formats to satisfy the diversity of learners in the classroom.

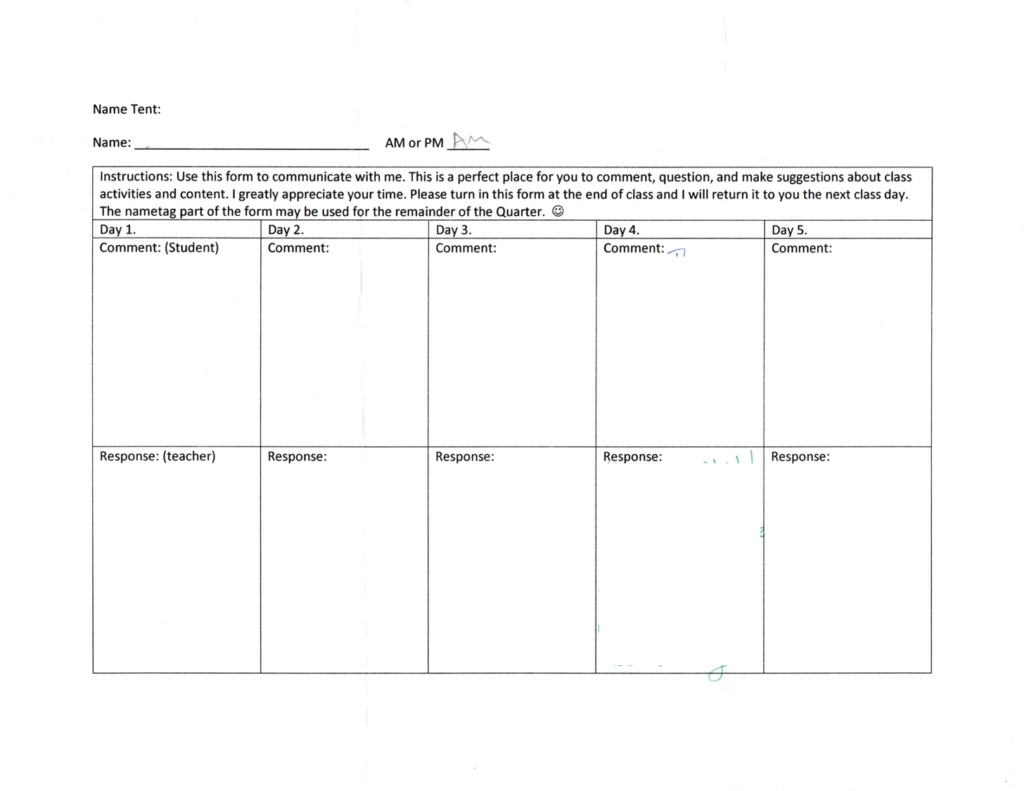

The students I worked with in my Chemistry 11 classroom ranged greatly in their individual strengths and focus; therefore, it was especially important for me to provide multifaceted formats for learning and to be able to confidently handle all types of questions and confusions associated with the chemistry concepts. What went well during my practicum was my ability to quickly create connections with students as individuals, obtain feedback on their learning, and then use this feedback to adapt lessons going forward. It quickly became clear to me that building relationships and trust with students was going to be a tool that could increase learning efficiency. Through simply knowing students’ names, classroom management became easier. For example, when certain students became talkative during lessons, I could use their name in examples or analogies to gain their attention without directly telling them to “stop talking.” Because the students already had familiarity with each other and my CT, I used something called “Name Tents” to expedite the processes of making individual connections. The Name Tents serve two functions: they act as an identifier and as a communication tool. Name Tents are folded pieces of paper (in a standing tent-shape) where students write and decorate their names, and then display them at their spaces. On the inside of the “tent” is a location for student comments and teacher responses. Near the end of each class, I provided students with a prompt to comment on in their Name Tents (I.E. What is one thing you would like me to know about you? If you could have a conversation with anyone—dead, alive, or fictional—who would it be? What from today’s lesson worked well for your learning? Etc.) which I would respond to and return to them the following day. After a single use of the Name Tents, I went from teaching in a classroom of strangers to having students stay after class and engage me in excited conversation over like-interests (music, cars, “The Peaky Blinders”). An advantage of this activity, in addition to building relationships through individual communication, was that the focus of the prompts could be shifted away from personal inquiry to educational inquiry and a tool for students to report feedback.

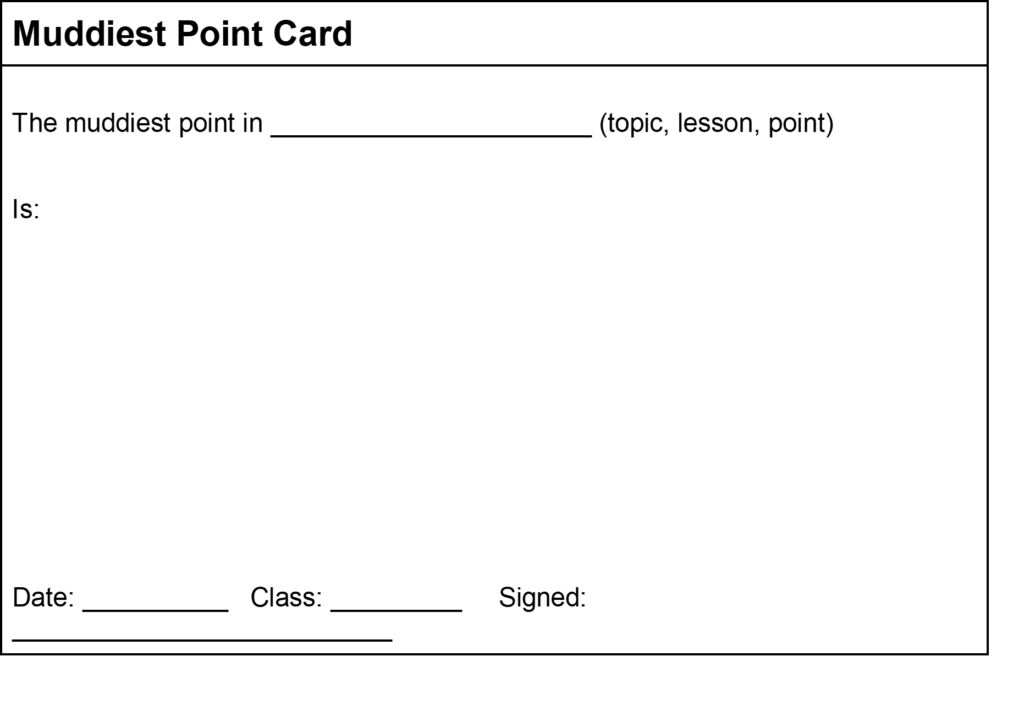

To help exemplify how I obtained and used formative assessment and feedback to enhance learning during my practicum, I will describe some of the tools I used during the bonding unit. The delivery of content for this unit was done through note packages that I created using information from multiple textbooks and additional resources. As far as note packages go, I created them to be as dynamic as possible. They included fill-in-the-blank sections, images, drawing sections, diagrams, analogies, textbook-definitions, student definitions, predictions, pattern recognition, practice problems (with extending questions) and more. Within these notes, I wrote prompts that would have students get into assigned, numbered groups of three and go to a corresponding numbered whiteboard in the room and work through problems. The use of whiteboards was based on the Vertical Non-Permanent Surfaces (VNPS) methodology in Thinking Classrooms proposed by SFU professor of education, Peter Liljedahl. His methodologies also include a “visibly random groups” component that was not utilized because of the current COVID-grouping restrictions in classrooms. The nine circumferentially located whiteboards provided me with an efficient route to circulate and acquire feedback on student understanding and provide differentiated learning assistance. It also allowed me the opportunity to use groups of students who were successfully completing problems as peer-learning resources for groups who were having difficulty and waiting for assistance. During the lesson on polar covalent bonds and molecular polarity, the student work displayed on the whiteboards revealed that I had underestimated the time it would take to cover this concept. In addition to using feedback from whiteboards, students were asked to complete a “Muddiest Point Card” (below) as an exit slip at the end of class.

Over that weekend, I used the Muddiest Point cards to create a focused assignment that had students progressively work towards conceptualizing polarity. The assignment had students clearly demonstrate an understanding of symmetry and used familiar concepts like directional force to conceptualize how electronegative atoms pull electron density. It also had students use molecular modelling kits to build the molecules they were describing geometrically. The assignment was marked formatively and returned to students with no grade but a great deal of feedback. Students were subsequently provided an “Understanding Check-In” which was a formative quiz based on the material from the whiteboards and assignment. Students were asked to treat this like a quiz when writing but understood explicitly that they would be marking it and that it would not affect their grade—rather it would be used to help focus the upcoming review for the summative unit test. I created the quiz such that each question addressed a specific component of their learning (symmetry, Lewis structures, bonding based on electronegativity, partial charges, etc.); it was then easy to tally up each section and weight the review appropriately. Review materials included conceptual checklists of everything we had gone over, practice problems, Phet simulations, educational videos, molecular modeling kits, Plickers multiple choice questions, and a lab that I co-created with my CT to have students apply the theory learned, but summatively assessed them on two curricular competencies. The Plickers application was a particularly valuable formative tool because it provided and saved immediate graphical class data of student answers and survey questions which was easily used to adjust weighted focus of learning.

Throughout practicum, phrases like “it’s not what you say, it’s what they do,” and “pre-assessments, formative assessments, and feedback are only valuable if they are applied to the learning” continuously occupied my mind. Tools like the Name Tents, exit slips, Plickers and others mentioned above allowed me to robustly adapt my teaching to fit the needs of the class and individuals. Although I am only just beginning the practice of extracting and using classroom data to facilitate education, I believe that I effectively implemented ongoing, bidirectional learning and that it had a positive result for the students, and myself as a developing educator.

During practicum, I spent a lot of time working towards refining my pacing. Even prior to starting practicum, I predicted that the pacing would be a component of teaching that would need to be worked out through experience. Although I am very capable of estimating the time it would take me to lecture a presentation to a group of people, teaching includes more unknowns than I was able to predict prior to starting. I also began my first day of teaching without having any clarity as to what these Chemistry 11 students did know, should know, and could know. For example, I anticipated teaching the concept of polarity would take no more than 30 minutes for the majority of the class to understand; in reality, it took several days with a great deal of different learning tools.

During the first week, it quickly became clear that a great deal of classroom efficiency was lost when transitions within lessons were sloppy and that the energy and mental state of the class greatly influenced learning efficiency. On my second day of practicum, my CT offered me some suggestions for material to get through and I created a lesson plan containing 8 or 9 components to fit into 1.3 hours in hopes of satisfying her recommendation. Not only did I not reach my pacing goal, but the learning also felt rushed, superficial, and ineffective—it felt terrible. Afterwards, I refused to attempt to cram lessons like I did that Tuesday, for the sake of the students and my own sanity. During student labs, I realized how the way in which the classroom was arranged influenced temporal efficiency. For example, by effectively spacing laboratory components, like materials, equipment, and waste containers, in the classroom, I could reduce the bottlenecking effect where students would waste time waiting. During each subsequent lab, I worked on refining the classroom layout and on techniques to keep students engaged and on track.

As I continue my development as a professional educator, I will increasingly become better at pacing. The use of timers, increasing familiarity around teaching certain concepts, viewing pacing through a holistic lens, and the physical set-up of classrooms are all items I am working towards refining in terms of increasing my ability to precisely plan lesson pacing.

As this semester concludes and the next begins, I approach the 490 practicum. During 391, I produced multiple assessment rubrics and had the opportunity to play around with several different assessment approaches; however, assessment was not the focus of the 391 practicum, and I was therefore not responsible of the overall assessment and reporting. Furthermore, there was a somewhat explosive situation that arose in response to students receiving their interim reports during my practicum. It demonstrated a strong disconnect between the function of holistic assessments based on proficiency scales and the percentage and grade-based reporting system on interims. As this experience appears in other writings, it will not be detailed here. The takeaway, however, is that I was able to observe how the practice and development of certain assessment styles could robustly represent learning, but without explicit understanding among the students, parents, and teachers, assessment can halt learning in its tracks and provoke anxiety, anger, and ego. I am curious as to how assessment strategies that are unfamiliar to students are best approached from the start and how evidence of learning is best documented by teachers for parents, students, and admin.

Leave a Reply